Just a few moments before, the angel Gabriel declared: “The prince of the kingdom of Persia withstood me one and twenty days: but, lo, Michael, one of the chief princes, came to help me; and I remained there with the kings of Persia” (Daniel 10:13). “Gabriel had been wrestling with the powers of darkness (while Daniel “was mourning three full weeks” [Daniel 10:2]) and seeking to counteract the influences at work on the mind of King Cyrus (“the prince of the kingdom of Persia” [Verse 13]). Before the contest closed, Christ himself came to Gabriel’s help. All that heaven could do on behalf of the people of God was done. The victory was finally gained, and the forces of the enemy were held in check all the days of Cyrus, who reigned for seven years, and all the days of his son Cambyses, who reigned about seven years and a half.” [1]

After that, he told Daniel: “I will shew thee that which is noted in the scripture of truth: and there is none that holdeth with me in these things but Michael your prince.” (Daniel 10:21)

Verse 1: Also I in the first year of Darius the Mede, even I, stood to confirm and to strengthen him.

“This verse is a continuation of the angel’s statement in ch. 10:21. The chapter division at this point is unfortunate. It gives the false impression that a new part of the book begins here, when the narrative is clearly continuous.” [2]

false impression that a new part of the book begins here, when the narrative is clearly continuous.” [2]

Therefore, the personal pronoun “I” denotes Gabriel as the speaker who had just “touched” Daniel and “strengthened” him, telling him he was “greatly beloved” and announced that he had “come to make [Daniel] understand what shall befall thy people in the latter days: for yet the vision [chazown] is for many days” beyond the “mar’eh.” (see Daniel 8:26; 10:14)

Although he had just strengthened Daniel, who had collapsed after hearing that announcement, and “touched” him (Daniel 10:18), Gabriel is here speaking of the time he “stood to confirm and to strengthen” “Darius the Mede” during his “first year” [3], just after he “took the kingdom” of Babylon away from Belshazzar (see Daniel 5:31; 6:1). That had to be the same year Darius “commanded and they brought Daniel, and cast him into the den of lions” then he “went to his palace, and passed the night fasting . . . and his sleep went from him” (Daniel 6:16, 18).

It was also the same year Daniel “set [his] face unto the Lord God, to seek by prayer and supplications, with fasting and sackcloth, and ashes” to understand the relationship between the 2300 “days” and the “seventy years in the desolations of Jerusalem” (Daniel 9:2, 3).

But now, all that was in the past. Daniel had resigned himself to the truth of the 2300 day “mar’eh” (Daniel 10:1), only to be discomfited by further revelations of the “chazown” (Daniel 10:14, 15). That revelation upset Daniel so much it became necessary for Michael and Gabriel to strengthen him to receive an even more clear revelation of what will culminate in “the time of the end” (see Daniel 8:17) when the “chazown” will be completely fulfilled.

Verse 2: And now will I shew thee the truth. Behold, there shall stand up yet three kings in Persia; and the fourth shall be far richer than they all: and by his strength through his riches he shall stir up all against the realm of Grecia.

Up to this point, “all that precedes, from chs 10:1 to 11:1, is background and introduction.” [4]

Gabriel, after reminiscing about his experience with Darius (Verse 1), gets back to what he had just said in Daniel 10:21, that he would “shew thee that which is noted in the scripture of truth.”

From that point on, he unfolds the extraordinary revelation of Chapter 11 and the first four verses of Chapter 12―fleshing out in astonishing detail the things represented symbolically in Daniel’s previous three visions in Chapters 2, 7 and 8! From Daniel’s perspective in time, all those things were detailed histories of the future. Daniel accepted them by faith. Now, we can have our faith in Gabriel’s revelation supported by the record of the past. But there is more to the story: “The prophecy of the eleventh chapter of Daniel has nearly reached its complete fulfillment. Soon the scenes of trouble spoken of in the prophecies will take place.” [5] “The prophecies of the eleventh of Daniel have almost reached their final fulfillment.” [6] But, that’s getting ahead of the story.

The “three kings in Persia; and the fourth” richest king were the successive line of rulers in the Persian kingdom, with Daniel himself serving as a cabinet member of the first king, Cyrus. Although Daniel could not have known their names, except for the first, history tells us that, after Cyrus, they were Cambyses, Cyrus’ son (530-522 B.C.), the False Smerdis (522 B.C.), Darius I (522-486 B.C.) and Xerxes (486-465 B.C.), the “Ahasuerus of the book of Esther.” [7] Xerxes is noted for his largely failed campaigns to conquer the Greeks by stirring up other nations, along with his, against them.

Although not alluded to in this line-up, Xerxes was followed by his son Artaxerxes (465-424 B.C.), who is featured in Ezra 7 as the king whose decree―the third after Cyrus’ decree (536/537 B.C.) and Darius’ decree (520 B.C.)― “gave the Jewish state full autonomy, subject to the overlordship of the Persian Empire” [8], to rebuild Jerusalem in 457 B.C., about eighty years after Cyrus’ decree, that Daniel must have thought was the beginning point of the 2300 “days.”

Centuries later, upon the retrospective analysis of history, [9] it has become abundantly clear that 457 B.C. was the beginning point of the “seventy weeks” of Daniel 9:24 and the 2300 days of Daniel 8:14. At that point, the 2300-day prophecy became a “definite” [10] time prophecy. Prior to that, in spite of Daniel’s belief that Cyrus’ decree in 537 B.C. was “definite,” it was actually “indefinite.” This is a very important principle (regarding time prophecies) for us to recognize.

Going back to Daniel’s previous visions, we are provided with more detail about the “chest and arms of silver” (Daniel 2), the “bear” (Daniel 7) and the “ram” (Daniel 8), all being parallel to the Persian Empire. [11]

Verse 3: And a mighty king shall stand up, that shall rule with great dominion, and do according to his will.

“This clearly refers to Alexander the Great (336-323 B.C.)” [12] whose campaign against Persia began with the battle of Granicus (334 B.C.). So, between the death of Artaxerxes in 424 B.C. and Alexander’s attack, 90 years had elapsed. During that

period of time, Artaxerxes was succeeded by his son Xerxes II who was assassinated only a few weeks later. Then, Darius II deposed that assassin and took the throne and ruled from 423 B.C. until his death in 404 B.C. He was succeeded by his son Artaxerxes II Memnon who ruled 46 years from 404 to 358 B.C., becoming the longest reigning of the Achaemenid (or Persian) kings.

He was succeeded by Artaxerxes III in 358 B.C. by the assassination of eight of his half-brothers. Interestingly, his death, twenty years later (338 B.C.) was the very year Philip of Macedon united the Greek states and so paved the way for his son Alexander. [13]

In the intervening time between Artaxerxes III’s death and Alexander’s initial attack, he was succeeded by Artaxerxes IV Arses who was poisoned by a man named Bagoas. Bagoas then had Darius III (336-330 B.C.) placed on the throne, but that did not ingratiate him with the king, because Darius forced Bagoas to swallow poison. Then, when Darius was just succeeding in subduing Egypt again, Alexander and his battle-hardened Macedonian troops attacked Asia Minor, which began the Wars of Alexander the Great. [14]

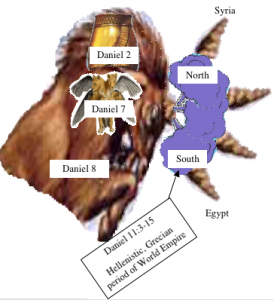

So, Alexander the Great, as we noted in Chapter 8, inaugurated the “brass” kingdoms of the great image of Daniel 2, the quad-headed “leopard” kingdom of Daniel 7, and the “he goat” kingdom of Daniel 8.

Verse 4: And when he shall stand up, his kingdom shall be broken, and shall be divided toward the four winds of heaven; and not to his posterity, nor according to his dominion which he ruled: for his kingdom shall be plucked up, even for others beside those.

With the pronoun “he” referring to Alexander the Great, only eleven years elapsed between the battle of Granicus in 334 B.C., when he began his campaign against Persia, and his death in 323 BC. The death of Alexander, the “mighty king,” is represented by “his kingdom” being “broken” just as the “great horn” of Daniel 8:8 that “was broken.” [15]

he began his campaign against Persia, and his death in 323 BC. The death of Alexander, the “mighty king,” is represented by “his kingdom” being “broken” just as the “great horn” of Daniel 8:8 that “was broken.” [15]

After Alexander’s demise, “his kingdom” was “divided toward the four winds of heaven” “representing the four quarters of the compass” [16], just as we noted in Daniel 8:8 where chance, rather than an appointed distribution of power, followed Alexander’s untimely death. Gabriel affirms that by saying that Alexander’s power was not transferred by appointment to his blood descendants or “posterity” or by his personal command but would be snatched up by the most able. [17]

At this point in Gabriel’s extraordinary narrative, his foresight had penetrated many years into the future. While Daniel had obviously accepted these things by faith, and conscientiously recorded what Gabriel told him, we can go back and check them out retrospectively by secular history and know with absolute certainty the details are accurate.

Verse 5: And the king of the south shall be strong, and one of his princes; and he shall be strong above him, and have dominion; his dominion shall be a great dominion.

Having identified the four “notable” kings who succeeded Alexander as Ptolemy, Seleucus, Cassander and Lysimachus (Daniel 8:8), Gabriel now focuses on the military campaigns conducted by two of the most notable antagonists of Alexander’s “Diadochi” called the kings of the north and the south. His discourse, in the next ten verses, will cover a period of time known in secular history as the Hellenistic period of world empire. [18]

Even though the Hellenistic period extends only to Verse 15, Gabriel continues referring to the kings of the “north” and “south” throughout the remainder of this chapter, suggesting Gabriel’s discussion will change from referencing literal kings to figurative “kings” or dominions.

So, this verse denotes the beginning of the ongoing conflict between the “king of the south” and the “king of the north” with neither attaining complete victory. The “king of the south” is clearly Ptolemy I Soter (323-283 B.C.), [19] one of the “Diadochi” [20] who was “founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty” of Egypt. In 305/304 B.C. he took the title of pharaoh. [21]

Gabriel then refers to “one of his princes” who would “be strong above him” or “later became stronger than” the southern king. [22] At first thought, “his prince” was one of his posterity, but not so, because the description fits that of Seleucus I Nicator (305-280 B.C.), another of Alexander’s generals, who made himself ruler of most of the Asiatic part of the empire.” [23] Why did Gabriel associate Seleucus with Ptolemy, as he seems to do here, saying he “shall be strong above him [Ptolemy]?”

Interestingly, Seleucus, shortly after the death of Alexander (323 B.C.), “felt himself threatened and fled to Egypt. In the war which followed . . . Seleucus actively cooperated with Ptolemy and commanded Egyptian squadrons in the Aegean Sea . . . The victory won by Ptolemy . . . in 312 B.C. opened the way for Seleucus to return to the east. His return to Babylon was afterwards officially regarded as the beginning of the Seleucid Empire . . .” [24] Although of little concern to secular historians, it was the start for “the king of the north.”

And Seleucus did become “strong above him [Ptolemy]” just as Gabriel predicted. He “acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia . . . Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tabouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus. So that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander . . . It is said of Seleucus that ‘few princes have ever lived with so great a passion for the building of cities.’” He “now held the whole of Alexander’s conquests except Egypt” only to be “assassinated by Ptolemy Keraunos” in 281 B.C.! [25]

Verse 6: And in the end of years they shall join themselves together; for the king’s daughter of the south shall come to the king of the north to make an agreement: but she shall not retain the power of the arm; neither shall he stand, nor his arm: but she shall be given up, and they that brought her, and he that begat her, and he that strengthened her in these times.

After the death of Seleucus I Nicator by assassination, he was succeeded by his son Antiochus I Soter (281-261 B.C.) and circumstances forced him to “make peace with his father’s murderer, Ptolemy Keraunos!” After his death, he was succeeded in 261 B.C. by his son Antiochus II Theos (261-246 B.C.), [26] but he inherited a state of war with Egypt. However, in time, he made peace with Ptolemy II of Egypt, ending the Second Syrian war. Antiochus II repudiated his first wife Laodice. Then, to seal the treaty, he married Ptolemy’s daughter Berenice and received an enormous dowry. But “By 246 B.C. Antiochus II . . . had left Berenice and her infant son in Antioch to live again with Laodice in Asia Minor.” Laodice took the occasion to poison Antiochus II while her partisans at Antioch murdered Berenice and her infant son. [27] [28]

So, filling in the blanks, “the king’s daughter of the south” was Berenice, the daughter of Ptolemy II of Egypt, and the “king of the north” was Antiochus II Theos. But “she (Berenice) shall not retain the power of the arm (or, those supposed to protect her would betray her), “neither” would “he (Antiochus) stand (that is he would fall) nor his arm (or those supposed to protect him): but she (Berenice) shall be given up (forsaken by Antiochus, or abandoned), and they that brought her (Berenice’s attendants who moved with her to Antioch?), and he that begat her (Bernice’s father, Ptolemy II of Egypt), and he that strengthened her (Antiochus?) in these times (during the time this all took place).” [29]

According to history, after Laodice had avenged herself of her humiliation, she then proclaimed her own son Seleucus II Callinicus king. [30] He reigned 21 years from 246 to 225 BC. [31]

Verse 7: But out of a branch of her roots shall one stand up in his estate, which shall come with an army, and shall enter into the fortress of the king of the north, and shall deal against them, and shall prevail:

While Laodice felt satisfied, feeling she was vindicated, her deed was not forgotten by at least one member of Berenice’s family, in fact, a rather important member. He was the son of Ptolemy II, “Ptolemy III Euergetes” who reigned 24 years from 246 to 222 B.C. following the death of his father. [32] Burning with vengeance because of Laodice’s dastardly deed in the murder of his eldest sister Berenice, Ptolemy III invaded Syria.

Verse 8: And shall also carry captives into Egypt their gods, with their princes, and with their precious vessels of silver and of gold; and he shall continue more years than the king of the north.

During this war called the “Third Syrian War [33] . . . he [Ptolemy III] occupied Antioch . . . and even reached Babylon” [34] just as Gabriel predicted that he would do, about 290 years before it happened! “The Ptolemaic kingdom was at the height of its power.” [35]

According to Gabriel, it was also a lucrative foray. That detail is a little hard to pin down from a web search, but the authors of the Commentary note: “Jerome states that Ptolemy III brought back immense booty to Egypt.” [36] Maxwell goes on to say “Ptolemy III captured 2500 gold and silver images, many of them being Egyptian gods that had been stolen by a succession of conquerors over the centuries . . . the Egyptians were delighted at what their Greek king had achieved for them, and they hailed him as their benefactor. In Greek ‘benefactor’ is ‘euergetes’ hence Ptolemy III Euergetes.” [37]

The final detail of Verse 8, saying Ptolemy “shall continue more years than the king of the north,” is true, since Seleucus II died after a fall from a horse [38] in 225 B.C. and Ptolemy III Euergetes died three years later in 222 B.C. That seems a minor detail for Gabriel to allude to. Other translations read: “And for years he shall stand away from the king of the north.” [39] Another: “and for many years afterwards he will leave the Syrian king alone.” [40] “Ptolemy III Euergetes was quite satisfied with himself after his profitable foray, and didn’t attack the Syrians again as long as he lived,” [41] which seems to be the basic thrust of the next verse.

Verse 9: So the king of the south shall come into his kingdom, and shall return into his own land.

This verse seems to repeat what we just learned in Verse 8, but there are differences of translation such as: “and he shall come into the realm of the king of the south, but he shall return into his own land” (ASV). Another reads: “The king of the North shall then invade the realm of the king of the South, but he shall retreat to his own country” (Moffat). Still another reads: “Then the king of the North will invade the realm of the king of the South, but will retreat to his own country” (NIV).

The Commentary agrees, saying: “the verse is doubtless to be interpreted as a reference to the fact that after Ptolemy III had returned to Egypt, Seleucus re-established his authority and marched against that country, hoping to retrieve his riches and regain his prestige.” But “Seleucus was defeated and forced to return to Syria empty-handed (about 240 BC).” [42]

Verse 10: But his sons shall be stirred up, and shall assemble a multitude of great forces: and one shall certainly come, and overflow, and pass through: then shall he return, and be stirred up, even to his fortress.

According to Maxwell, Verses 10 to 12 “deal principally with the battle of Raphia, June 22, 217 B.C.” [43] Although secular historians may not have considered it to be a fulfillment of Gabriel’s prophecy, they agree that the battle of Raphia was “fought on 22 June 217 BC near modern Rafah between the forces of Ptolemy IV Philopator, king and pharaoh of Ptolemaic Egypt and Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire.” [44] [45]

This brings up an important point: Why was Gabriel so interested in this battle, or, for that matter, all the other battles he refers to in Chapter 11? Several reasons come to mind, but primarily, it would seem, battles are permanently etched into the minds of men who lived in the times they were fought and are not easily forgotten even by successive generations, especially those employing historians who research the annals of human history. For that one reason alone, it would seem Gabriel capitalized on that fact in order to facilitate tracking the extraordinary accuracy of his predictions; thus, confirming the faith of those who choose to believe God.

facilitate tracking the extraordinary accuracy of his predictions; thus, confirming the faith of those who choose to believe God.

Getting back to the subject introduced in Verse 10, we find that Seleucus II had two sons: “Seleucus III Ceraunus Sorter (226-223 B.C.), who was murdered after a short reign, and Antiochus III, the Great (223-187 B.C.).” Antiochus III must be the “one” [46] who “shall certainly come [47] . . .” or “attack the enemy,” therefore initiating “his campaign for southern Syria and Palestine by retaking Seleucia, the port of Antioch . . . from his rival, Ptolemy IV Philopator (221-203 B.C.), during which he penetrated Transjordan.” [48] So, in the initial phase of this battle, Antiochus III won, hands down. But that was not the end of the story.

Verse 11: And the king of the south shall be moved with choler, and shall come forth and fight with him, even with the king of the north: and he shall set forth a great multitude; but the multitude shall be given into his hand.

The wording here is a bit tricky. The “king of the south” was Egypt’s Ptolemy IV Philopator who ruled 17 years from 221 to 204 B.C. Being “moved with choler” [49] or enraged, he mounted a counterattack. So, “the king of the north,” Antiochus III, defended himself with “a great multitude” [50] that was “given into ‘Ptolemy’s’ hand.” [51] [52] In other words, Ptolemy IV won his counterattack against Antiochus III.

Verse 12: And when he hath taken away the multitude, his heart shall be lifted up; and he shall cast down many ten thousands: but he shall not be strengthened by it.

In the battle of Raphia, both sides sustained heavy losses of horses and elephants, but, while Antiochus III had lost 10,000 foot soldiers, Ptolemy IV lost only 1,500. [53] In the aftermath, as Gabriel prophesied, Ptolemy gained “little in the long run. He was a notorious debauchee. He failed to follow up the success his generals had handed him—and Antiochus III was eager for a rematch.” [53A]

Interestingly, Ptolemy IV was always under the dominion of favorites who indulged his vices and conducted the government as they pleased. Self-interest led his ministers to make serious preparations to meet the attacks of Antiochus III, followed by the great Egyptian victory of Raphia where Ptolemy IV himself was present. That victory secured the northern borders of the kingdom for the remainder of his reign. [54]

Nevertheless, Ptolemaic kings, descendants of their Greek ancestors, were “viewed by the local Egyptians with nothing more positive than resentful acquiescence . . . Thus, the Egyptians needed only a weakening of control at the top to produce a whole string of violent insurrections . . . Unlike his predecessors, this Ptolemy (IV) led a dissolute life . . .” He even “agreed to have his mother . . . and his brother respectively poisoned and scalded to death within a year of his ascension” [55] in 221 B.C.!

Verse 13: For the king of the north shall return, and shall set forth a multitude greater than the former, and shall certainly come after certain years with a great army and with much riches.

This is Antiochus III again who had been spoiling, for the past ten years, for another fight with Egypt, during which he busied himself restoring the eastern part of his rebellious dominion to himself. [56] Returning to the west in 205 B.C., he found that Ptolemy IV had died leaving things in the hand of his child, Ptolemy V Epiphanies (205-180 B.C.) who was only five years old. Antiochus III then made a compact with Philip V of Macedon to divide the Ptolemaic possessions outside of Egypt. They were successful in what is called “The fifth Syrian War” when the Seleucids ousted Ptolemy V from control of the southern region of Syria, including Judea, [57] in the battle of Panium, near Caesarea Philippi, in 200 B.C. [58]

Verse 14: And in those times there shall many stand up against the king of the south: also the robbers of thy people shall exalt themselves to establish the vision [chazown]; but they shall fall.

While “the first thirteen verses of Daniel 11 have been minutely fulfilled . . . verses 14-39, however, have occasioned a variety of expositions.” [59] Even worse, the “interpretations of the remainder of [Chapter 11] differ widely.” [60] Therefore, from this point onward, we will be obliged to depend on the leading of the Holy Spirit as we examine even more closely Gabriel’s discourse as recorded by Daniel.

Some believe the phrase “in those times” refers to a continuation of “the subsequent history of the Seleucid and Ptolemaic kings” while others suggest “that with v. 14, the next great world empire, Rome, enters the scene.” [61] Therefore, while multiple options are open to us, we must do our best to base them on adequate evidence.

The phrase “in those times” opens up a broad sweep of history with many events taking place during and after the “times” of Ptolemy V Epiphanies and the time Rome comes into the picture.

Among the “many” who stood up “against the king of the south” would include “those Egyptians . . . who were rebelling against their Greek overlords.” [62] The guerillas were the original Egyptian troops who received their training from Ptolemy V’s father Ptolemy IV, to defeat Antiochus III in the battle of Raphia. Even though they helped Ptolemy IV defeat Antiochus III, they still craved independence from their Greek rulers. Eventually they were able to achieve total independence in the south of Egypt and be ruled once more by native pharaohs. That caused a lot of trouble for Ptolemy V. It seems he was forced to increase his army of mercenaries (which was expensive), draining his capitol resources and resulting in a cutback in overseas trade and further deterioration in the economic situation [63] of Egypt.

Gabriel, saying “also,” suggests another scenario was taking place at the same time. He reflects on “the robbers of [Daniel’s] people” who would “exalt themselves to establish the vision [chazown].” [64] This is significant because those who were to “stand up against” Ptolemy could not be expected to have any interest in or even any knowledge of the Daniel’s “vision [chazown]” (Daniel 8:17, 26).

So, who were those robbers? Self-exaltation is a common characteristic, but exalting themselves to “establish the vision [chazown]” proves they had to be Jews, for no other people would have any idea what the “chazown” was. Also, they would have to be students of Daniel’s prophecies, especially where Gabriel declared “at the time of the end shall be the vision [chazown]” (Daniel 8:17) and the “seventy weeks” during which the Jews were expected to “seal up the vision [chazown] and prophecy, and to anoint the most Holy” place (Daniel 9:24). They probably ignored the 2300 day “mar’eh” of Daniel 8:14 [65] which extended far beyond their time, little realizing that the “chazown” reached “many days” (Daniel 8:26 last part) even beyond that! [66] So, because they were committed to “exalt themselves” instead of God, right from the start, they were destined to “fall.”

Although Gabriel says nothing about the “king of the north” at this point, the Commentary alludes to the “threat posed by Antiochus [IV] Epiphanes” [67] who “ruled the Seleucid Empire from 175 BC until his death in 164 BC.” [68] Therefore, his rule began very soon after the death of Ptolemy V in 180 B.C. Secular history affirms that notable events during the reign of Antiochus IV “include his near-conquest of Ptolemaic Egypt . . . and the rebellion of the Jewish Maccabees.” [69]

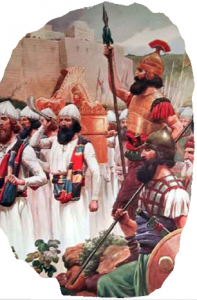

Antiochus IV forced the Jews “to erect pagan altars in every Judean town, to offer swine’s flesh upon them, and to surrender every copy of their Scriptures to be torn up and burned. Antiochus [IV] also set up a heathen idol on the Temple altar in Jerusalem and offered swine’s flesh upon it . . . the prospect that the Jewish religion might survive, or that the Jews could preserve their identity as a people, seemed dim . . . Eventually the Jews rose in revolt and drove the forces of Antiochus [IV] from Judea. They even succeeded in repelling an army sent by Antiochus [IV] for the specific purpose of exterminating them as a nation. Free once more from his oppressive hand, they restored the Temple, set up a new altar, and again offered sacrifice.” [70]

Therefore, it seems clear that “the robbers of thy people” were the Maccabees who rose up to smite the oppressor in 167 B.C. under “Mattathias, the Hasmonean” who “together with his five sons fled to the wilderness of Judea after he slew a Hellenistic Jew who stepped forward to offer a sacrifice to an idol in Mattathias’ place. After Mattathias’ death about one year later, his son Judah Maccabee led an army of Jewish dissidents to victory over the Seleucid dynasty . . . After the victory, the Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph and ritually cleansed the Temple . . . A large Syrian army was sent to quash the revolt, but returned to Syria on the death of Antiochus IV. Its commander Lysias, preoccupied with internal Syrian affairs, agreed to a political compromise that provided religious freedom.

“Mattathias, the Hasmonean” who “together with his five sons fled to the wilderness of Judea after he slew a Hellenistic Jew who stepped forward to offer a sacrifice to an idol in Mattathias’ place. After Mattathias’ death about one year later, his son Judah Maccabee led an army of Jewish dissidents to victory over the Seleucid dynasty . . . After the victory, the Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph and ritually cleansed the Temple . . . A large Syrian army was sent to quash the revolt, but returned to Syria on the death of Antiochus IV. Its commander Lysias, preoccupied with internal Syrian affairs, agreed to a political compromise that provided religious freedom.

“Following the re-dedication of the temple, the supporters of the Maccabees were divided over the question of whether to continue fighting or not. When the revolt began under the leadership of Mattathias, it was seen as a war for religious freedom to end the oppression of the Seleucids. However, as the Maccabees realized how successful they had been, many wanted to continue the revolt and conquer other lands with Jewish populations or to convert their peoples. This policy exacerbated the divide between the Pharisees and Sadducees [71] under later Hasmonean monarchs such as Alexander Jannaeus. Those who sought the continuation of the war were led by Judah Maccabee.

“On his death in battle in 160 BCE, Judah was succeeded as army commander by his younger brother, Jonathan, who was already High Priest. Jonathan made treaties with various foreign states, causing further dissent among those who merely desired religious freedom over political power. On Jonathan’s death in 142 BCE, Simon Maccabee, the last remaining son of Mattathias, took power. That same year, Demetrius II, king of Syria, granted the Jews complete political independence and Simon, great high priest and commander of the Jews, went on to found the Hasmonean dynasty. Jewish autonomy lasted until 63 BCE, when the Roman general Pompey captured Jerusalem and subjected Judea to Roman rule, while the Hasmonean dynasty itself ended in 37 BCE when the Idumean Herod the Great became de-facto king of Jerusalem.” [72]

Verse 15: So the king of the north shall come, and cast up a mount, and take the most fenced cities: and the arms of the south shall not withstand, neither his chosen people, neither shall there be any strength to withstand.

This verse resumes the scenario of Verse 13 that was interrupted by the parenthetical remarks of Verse 14. It continues with the narrative of Verse 13 concerning Antiochus III’s second campaign in Palestine after he had lost to Ptolemy IV in the battle of Raphia. Now having at his behest “a great army [73] and with much riches” (v. 13), he takes control of the “most fenced cities” or “a city of fortifications [74] erected by Ptolemy IV of Egypt to defend his holdings in Syria. As this verse indicates, Ptolemy V, ruler of Egypt, is finally defeated. [75]

Verse 16: But he that cometh against him shall do according to his own will, and none shall stand before him: and he shall stand in the glorious land, which by his hand shall be consumed.

Note, the personal pronouns “he, him, his,” used six times in this verse! This challenges our ability to concentrate and keep things straight.

Therefore, at this point, and throughout the remainder of Chapter 11, Gabriel repeatedly uses these pronouns with only occasional reference to specific subjects such as the “king of the south/north” in contrast to what we find in Verses 1-15 where the subjects of the pronouns are clearly defined.

The first pronoun “he,” in Verse 16 depicts the entrance of a new power in the scenario of Verses 1-15 because “he” can do anything “according to his own will,” and “none” can oppose him. Therefore, “he” is far stronger than either the “king of the north” or the “king of the south.” The only “king” that coincides with such a description must be Rome who, geographically speaking, came from the west! In effect, he breaks up the power struggle between Syria, lying to the north of Palestine, and Egypt to the south.

Then, the next pronouns “him,” whom “he” came “against must be the “king of north of Verse 15. While Antiochus III was the one whose activity was spoken of there, by the time the northern king and Rome confronted each other, as in Verse 16, another king had taken the place of Antiochus III.

How it all happened, is very interesting. The successor of Antiochus III was Seleucus IV Philopater, who ruled 12 years from 187 to 175 B.C. [76] He was compelled by financial necessities, created in part by the heavy war-indemnity exacted by Rome, to pursue an ambitious policy. In an effort to collect money to pay the Romans, he sent his minister Heliodorus to Jerusalem to seize the temple treasury. On his return, Heliodorus assassinated Seleucus, and seized the throne for himself.

The true heir Demetrius, son of Seleucus, now being retained in Rome as a hostage, the kingdom was seized by the younger brother of Seleucus, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, who managed to oust Heliodorus, even though an infant son, also named Antiochus, was formal head of state for a few years until Epiphanes had him murdered. [77]

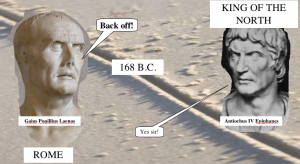

This story takes us full circle back to the same king of the north (Antiochus IV) who gave the Maccabees cause for the revolt we just read about in Verse 14. Interestingly, another notable event during his reign was his near conquest of Egypt, which lead to a confrontation that became an origin of the metaphorical phrase, “line in the sand.” [78]

“In 168 B.C., a Roman Consul named Gaius Popillius Laenas drew a circular line in the sand around King Antiochus IV of the Seleucid Empire, then said, ‘Before you cross this circle I want you to give me a reply for the Roman Senate’ – implying that Rome would declare war if the King stepped out of the circle without committing to leave Egypt immediately. Weighing his options, Antiochus wisely decided to withdraw. Only then did Popillius agree to shake hands with him.” [79] [80]

Again, Gabriel’s prophecy, given 369 years in advance, predicted “he that cometh against” Antiochus IV would be Rome, and as proven by history, nobody else was ever able to “stand before” Rome for the next 644 years until 476 A.D.!

But that was not the last of Gabriel’s predictions about Rome in Verse 16. He went on to say that Rome would “stand in the glorious land” [81] and it would “be consumed” “by his hand,” the catastrophe Gabriel predicted in Daniel 9:26: “the prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary.” That part of the prophecy was fulfilled in 70 A.D. when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans.

At this point in Verse 16, we come to the transition period between the “brass” and the “iron” in Chapter 2, and the “leopard” and the “fourth beast in Chapter 7. It also brings us to the end of the four horned, Hellenized “goat” of Daniel 8, even though Gabriel fails to mention a parallel to the “fourth beast” except to allude somewhat vaguely to “the transgressors [that] are come to the full” (Daniel 8:23), a gap between Greece and the “little horn” or “king of fierce countenance” representing papal, not pagan, Rome. But Verses 16 to 20 of this chapter fill in that gap very nicely.

At this point in Verse 16, we come to the transition period between the “brass” and the “iron” in Chapter 2, and the “leopard” and the “fourth beast in Chapter 7. It also brings us to the end of the four horned, Hellenized “goat” of Daniel 8, even though Gabriel fails to mention a parallel to the “fourth beast” except to allude somewhat vaguely to “the transgressors [that] are come to the full” (Daniel 8:23), a gap between Greece and the “little horn” or “king of fierce countenance” representing papal, not pagan, Rome. But Verses 16 to 20 of this chapter fill in that gap very nicely.

Verses 17 – 19: He shall also set his face to enter with the strength of his whole kingdom, and upright ones with him; thus shall he do: and he shall give him the daughter of women, corrupting her: but she shall not stand on his side, neither be for him. After this shall he turn his face unto the isles, and shall take many: but a prince for his own behalf shall cause the reproach offered by him to cease; without his own reproach he shall cause it to turn upon him. Then he shall turn his face toward the fort of his own land: but he shall stumble and fall, and not be found.

Note the pronouns “he, him, his” and now “her” are used 21 times in these verses. While “her” obviously refers to “the daughter of women,” the masculine “he, him” and “his,” being the antecedent to the Roman “he” in Verse 16, “he” in these verses is still Rome.

But, because “he, him, and his” sets “his face” and turns “his face” [82] one direction then another to exert “the strength of his . . . kingdom” and conquer “many” other kingdoms and then retreat back to “the fort of his own land” and, seemingly, disappear, all this is descriptive of the character and behavior of a single, individual person, rather than a whole kingdom.

“He” would also be an individual citizen of Rome, engaged in conquering other nations and, therefore, a general in the armies of Rome. Consequently, Julius Ceasar (100 – 44 B.C.), who engaged in an illicit affair with Cleopatra VII Philopater (69-30 B.C.) is the only person whose life’s record corresponds with the details Gabriel sets forth in Verses 17-19.

History acknowledges that Julius Ceasar played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. [83] Likewise, Cleopatra’s reign, as a Hellenistic ruler of Egypt, marks the end of the Hellenistic Era and the beginning of the Roman Era in the eastern Mediterranean [84], which from Gabriel’s perspective represented an important phase in the transition from the “brass” to the “iron” of Chapter 2, and from the “leopard” to the “fourth beast” of Chapter 7.

Verse 20: Then shall stand up in his estate a raiser of taxes in the glory of the kingdom: but within few days he shall be destroyed, neither in anger, nor in battle.

The words Gabriel uses in Verse 19, where Julius Caesar “shall stumble and fall,” must refer to his assassination in 44 B.C. His assassins had hoped to be received as liberators from what they thought was Caesar’s ambition to become a king. So, “after the assassination, Brutus [one of the leading conspirators] stepped forward as if to say something to his fellow senators; they, however, fled the building. Brutus and his companions then marched to the Capitol while crying out to their beloved city: ‘People of Rome, we are once again free!’ They were met with silence, as the citizens of Rome had locked themselves inside their houses as soon as the rumour of what had taken place had begun to spread.” [85]

The result, unforeseen by the assassins, was that Caesar’s death precipitated the end of the Roman Republic. The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular became enraged that a small group of aristocrats had killed their champion. A man by the name of Antony capitalized on the grief of the Roman mob, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself. To his surprise and chagrin, Caesar had named his grandnephew Gaius Octavian his sole heir, bequeathing him the immensely potent Caesar name and making him one of the wealthiest citizens in the Republic.” [86]

“On 16 January 27 BC the Senate gave Octavian the titles of augustus and princeps. Augustus is from the Latin word augere (meaning to increase) and can be translated as “the illustrious one”. It was a title of religious authority rather than political authority.” He is known for being “the founder of the Roman Principate, which is the first phase of the Roman Empire,” and is considered to be “one of the greatest leaders in human history.” [87]

So, this must be the man whom Gabriel called “a raiser of taxes.” Centuries later, Luke the apostle wrote “that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed . . . And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judaea, . . .To be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child” (Luke 2:1, 4, 5).

Gabriel then goes on to say, “within few days he shall be destroyed” but not “in anger, nor in battle.” “On 19 August AD 14, Augustus died while visiting Nola where his father had died. Augustus’s famous last words were, ‘Have I played the part well? Then applaud as I exit’ (“Acta est fabula, plaudite”) —referring to the play-acting and regal authority that he had put on as emperor. . . An enormous funerary procession of mourners traveled with Augustus’s body from Nola to Rome . . .Tiberius [his adopted son who succeeded him] and his son Drusus delivered the eulogy.” [88] Just as Gabriel predicted, his death was peaceful, but, since Augustus’ rule lasted at least 41 years, why did Gabriel say he would “be destroyed” “within few days.”

The verb “destroyed” is translated from the Hebrew word “shabar” [89] meaning “to be broken, maimed, crippled” or “wrecked.” While “shabar” is usually used in the active sense, it, depending on the context, can be used passively as well. For example, “the great horn was broken [“shabar”]” (Daniel 8:8) passively when Alexander the Great died, not by anger nor in battle, but from physical debility.

Likewise, while the 41 years of Augustus’ rule seems lengthy to us, it certainly seemed “few” from Gabriel’s perspective, reminding us of the brevity of time for all who live, whether the span of life can be measured in decades or minutes. Also, it should be understood that the word “few” is from the Hebrew “’echad” [90] that is translated “few” only three times in the Bible, although it is used more than 900 times and, nearly always without reference to length or duration. A more appropriate translation could be “some.”

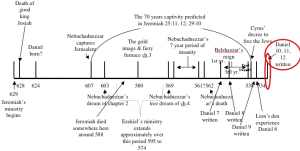

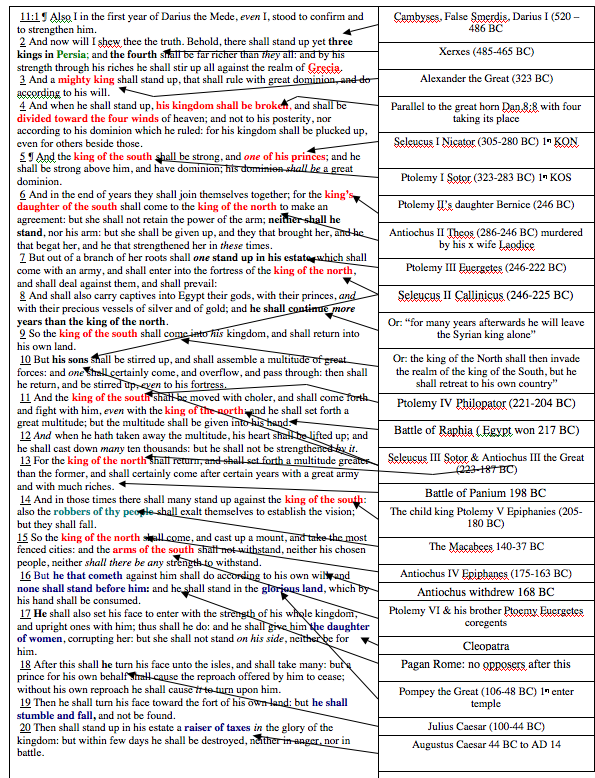

Summary of Daniel 11:1-20: Chapter 11, the longest in the book of Daniel, comprises a total of 45 verses. In this section we explore the first 20 verses which itemize, in marvelous accuracy, as verified by secular history, a series of predictions Gabriel made to Daniel in 536/537 B.C. “the third year of Cyrus.” These verses cover a period of some 563 years from 550 B.C. to 14 A.D., beginning with four future kings of Persia, then Greece, followed by pagan Rome, the same sequence of empires outlined in the image dream of Chapter 2, the beast vision of Chapter 7, and then the ram and goat vision of Chapter 8. Gabriel, in Verse 14, digresses from that sequence to speak briefly of the “robbers” of Daniel’s people who first make their appearance during the brass, ending up with the iron. This study suggests that they represent the Maccabees who began as freedom fighters from the Seleucids, then, during the iron, ending up becoming instrumental in robbing their nation of the Messiah.

Consider this diagram outlining the events of Verses 1-20 that Gabriel predicted long before they were fulfilled:

[1] E.G. White in Review and Herald, 12-5-07 (Parenthesis supplied)

[2] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 864 (under 1. Also I.”)

[3] Darius’ “first year” was 539 B.C., while this narrative was during “the third year of Cyrus” (Daniel 10:1) three to five years later. (see note #2, Daniel 10, for explanation of various dates)

[4] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 864 (under “2. The truth”)

[5] Testimonies for the Church by E.G. White, Vol. 9, page 14 (italics mine)

[6] Welfare Ministry by E.G. White, page 136 (italics mine)

[7] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 864 (under “Far richer.”) see also, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xerxes_I

[8] Ibid, page 853 (second paragraph left column)

[9] www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/denominationalfounders/william-miller.html

[10] The term “definite time,” that so often White warns against, is used some 83 times in her writings. Daniel’s perspective, thinking that 537 B.C. was “definite,” is certainly excusable. However, as we look forward to time prophecies, future to our time, such as the 1000 years of Revelation 20, all should be considered “indefinite” because, in every case, it is always impossible to establish a beginning point prospectively, with absolute certainty.

[11] By this time, the Medes, as well as Babylon, had been absorbed into the Persian Empire

[12] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 865 (under “3. A mighty king.”)

[13] I got all this interesting information from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Achaemenid_Empire

[14] Ibid. Some of this I copied, some I paraphrased. Anyway there were a lot of Persian kings who reigned during the 90 years between Artaxerxes I and Alexander the Great. But, that, in no way, discredits anything Gabriel said. He just hits the high points of history, a characteristic we will see more of as we get into the intriguing details of Daniel 11.

[15] The adverb “broken” in Daniel 8:8 and 11:4 comes from the same Hebrew word “shabar” (Strong’s #7665)

[16] see Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 866 (under “The four winds.”)

[17] Review the discussion of Daniel 8:8. No need to repeat it here

[18] The term Hellenistic itself is derived from the Greeks’ traditional name for themselves. It was coined by the historian Johann Gustav Droysen to refer to the spreading of Greek culture and colonization over the non-Greek lands that were conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th century B.C. There has been much debate about the validity of Droysen’s ideas; leading many to reject the label ‘Hellenistic’ (at least in the specific meaning of Droysen). However, the term Hellenistic can still be usefully applied to this period in history, and, moreover, no better general term exists to do so. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellenistic_civilization)

[19] Interestingly, while the Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Vol. 4, page 866), suggests 306-283 B.C.; Mervyn Maxwell (God Cares, Vol. 1, page 284) says 323-280; and Wikipedia says 323-283.

[20] Specifically, in Hellenistic history, the Diadochi were the rival successors of Alexander the Great and their wars that followed Alexander’s death. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wars_of_the_Diadochi)

[21] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_I_Soter

[22] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 866 (under “one of his princes”)

[23] Ibid

[24] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleucus_I_Nicator (italics mine)

[25] Ibid (even though the extent of his reign is said to end in 280 B.C.)

[26] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiochus_I_Soter

[27] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiochus_II_Theos

[28] see also God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 286

[29] I may not have that translation exactly right, but, anyway, it was an extraordinarily marvelous demonstration of Gabriel’s insight!

[30] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiochus_II_Theos

[31] see chart: God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 286

[32] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_III

[33] Also known as the Laodicean War” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syrian_Wars in “honor” Antiochus’ wife Laodice

[34] Ibid

[35] Ibid

[36] see Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 867

[37] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 287)

[38] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleucus_II_Callinicus

[39] the Hebrew interlinear

[40] The Tay version

[41] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 287

[42] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 867 (under “9. King of the south”)

[43] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 287

[44] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Raphia

[45] see also Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 868

[46] with the word “one” being italicized, and thus supplied, suggests it is unwise to use it as definitive for Antiochus. But, since history proves that the first son was killed, the “one” remaining has to be Antiochus III, the Great.

[47] “come” from: the qal of “bow’” (Strong’s #935) “to enter, come upon, fall, or light upon, attack (enemy)”

[48] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4 page 867 (bottom right column)

[49] “choler” from the Hithpalpel of “”marar” (Strong’s #4843) to embitter oneself; to be enraged”

[50] Antiochus’ army was composed of 5,000 light armed Daai, Carmanians and Cilicians under Byttacus the Macedonian, 10,000 phallangites with white shields (leukaspides) under Theodotos the Aetolian, the very one who betrayed Ptolemy and handed much of Coele Syria and Phoenicia over to Antiochus, 20,000 phallangites under Nicarchos and Theodotos, 2,000 Persian and Agrianian archers and slingers, 1,000 Thracians under Alavadeas Menedemon, 5,000 Medes, Kissians, Cardushians and Carmanians under the Mede Aspasian, 10,000 Arabians under Zavdevelon, 5,000 Greek mercenaries under Eurilochos and 1,000 Neocretans under Zelyn the Gortynian, 500 Lydian javelineers and 1,000 Kardakes under Lysimachus the Gaul. 4,000 horse under Antipatros, the nephew of the King and 2,000 under Thesmion formed the cavalry and 103 war elephants of the Indian stock marched under Philip and Myischos. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Raphia>

[51] The Commenatry explains the difficult wording in this verse in this way: “The antecedents of the various pronouns in this verse become clearer when it is recognized that the passage is in the form of a Hebrew inverted parallelism in which the first and fourth elements and the second and third, are in parallel. Thus in this verse the references are as follows: King of the south, king of the north, he (king of the north), his (king of the south).” Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 868 (top left column)

[52] Ptolemy had just ended a major recruitment and retraining plan with the help of many mercenary generals. His forces consisted of 3,000 phallangites under Eurylochos the Magnesian (the agema), 2,000 peltasts under Socrates the Boeotian, 25,000 phallangites under Andromachos the Aspendian and Ptolemy of Thraseos and 8,000 Greek mercenaries under Phoxis the Achaean and 2,000 Cretan and 1,000 Neocretan archers under Philon the Knossian. Ptolemy had also trained in the Macedonian way of warfare, which means as a sarissa bearing phalanx another 3,000 Libyans under Ammonios the Barcian and 20,000 Egyptians under his Prime Minister Sosivios. Apart from these he also had contigents of 4,000 Thracians and Gauls (from those who had dwellt for years or had been born in Egypt) and another 2,000 of the newcomers under Dionysus the Thracian.

His Household Cavalry (tis aulis) numbered 700 men and the local (egchorioi) and Libyan horse, another 2,300 men had as appointed general Polycrates and those from Greece and the mercenaries were led by Echecratis the Thessalian. Ptolemy’s force was accompanied by 73 elephants of the African stock. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Raphia>

[53] Ibid

[53A] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 288

[54] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_IV_of_ Egypt (bracket mine)

[55] http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/ptolemy4.htm

[56] see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleucid_Empire

[57] this area was called “Coele-Syria” meaning “hollow” Syria, the Beqaa Valley of Lebanon, often used to cover the entire area south of the river Eleutherus incliding Judea” (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coele-Syria)

[58] Ibid

[59] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 288

[60] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 868 (bottom left column under “14. In those times.”)

[61] Ibid (top right column)

[62] God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 288

[63] see http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/ptolemy4.htm, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemy_V_Epiphanes, ancient_egypt.en-academic.com/1008/Ptolemy_V Epiphanes

[64] “vision” from “chazown” (Strong’s #2377)

[65] At this point, if the reader is not familiar with the fact that the word “vision” in Daniel 8, is translated from two different Hebrew words “chazown” and “mar’eh,” go back and review our discussion of Chapter 8, if necessary. This is a very important point because Gabriel handles them differently even though it is difficult to distinguish the differences in the actual meanings of those two words. Obviously, from Daniel’s and Gabriel’s perspective, they were very different!

[66] This was almost 260 years after Artaxerxes Longimanus (465-423 B.C.) had issued the final decree in 457 B.C., enabling the Jews to complete the rebuilding of Jerusalem, which also marked the beginning of the 2,300 days. Evidently, they had not yet understood that God was not interested in helping them establish an earthly kingdom, an idea they, and those who came after, never abandoned.

[67] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 868 (right column second paragraph)

[68] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiochus_IV_Epiphanes

[69] Ibid

[70] Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 868 (right column parts of second, third and fourth paragraphs)

[71] My thought here: The Pharisees and Sadducees coincide admirably with the “robbers” for it was their malicious influence over the people that robbed the nation of its Messiah.

[72] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maccabees

[73] https://www.thecollector.com/antiochus-iii-the-great-seleucid-king/

[74] see Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, pages 868-869

[75] Op Cit

[76] See the very helpful list of Hellenistic kings in God Cares by Mervyn Maxwell, Vol. 1, page 286.

[77] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleucus_IV_Philopator. If you look up this site, you will notice that is infers that “Heliodorus” is the “tax collector” mentioned in Daniel 11:20, “He will send out a tax collector to maintain the royal splendor.'” But when we get to Verse 20, we will be forced to disagree with that statement.

[78] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antiochus_IV_Epiphanes

[79] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Line_in_the_sand_(phrase)

[80] Mervyn Maxwell tells the same story, although not in this context, in God Cares Vol. 1, page 159.

[81] “the glorious land . . . is Palestine . . . the conquest of Palestine here described is believed to be that of Pompey, who, in 63 B.C. intervened in a dispute between two brothers, Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, rivals to the throne of Judea.” (SDA Bible Commentary, Vol. 4, page 869 (right column under “16. Glorious land.”)

[82] the noun “face” is from: “paniym” (Strong’s #6440) “fact, faces, presence, person, face of seraphim or cherubim; face of animals; surface of ground” etc. In this case, it is clearly the “face” of a “person.”

[83] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Caesar

[84] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra

[85] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Caesar

[86] ibid (under “aftermath of the assassination)

[87] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus

[88] Ibid

[89] “destroyed” from the Niphal form of “shabar” (Strong’s #7665) “to be broken, be maimed, be crippled, be wrecked, be crushed.”

[90] “few” translated from “’echad” (Strong’s #259) Look it up. Daniel 11:20 is the only one of the three places in the Old Testament “’echad” is translated “few.” The other two are in Genesis 27:44 and 29:20. The other possible translations are as follows: “one 687, first 36, another 35, other 30, any 18, once 13, eleven + 06240 13, every 10, certain 9, an 7, some 7, misc.87; total = 952.” So, among all those options, what would be the best translation? Although I’ll have to leave it with the Hebrew scholar to make the final decision, perhaps the word “some,” used only 7 times, would be more appropriate.